span of attention

The second half of this century has seen the rise of three modes of electronic performance that happen to be short: the sitcom, the music video, and the sound bite. New forms always attract critics, and these three have never lacked for detractors. Many have argued that these forms are debased by their brevity, and that electronic media are responsible for shortening our attention spans. In some quarters. These popular genres are dismissed as superficial spectacles that titillate and numb the debased tastes of the masses.

In the same vein, New Media -- notably hypermedia -- are widely assumed to appeal to the same demands for spectacle and brevity. Multimedia edutainment, for example, is praised by its supporters for its appeal to the "MTV generation" while detractors decry youth's loss of immersion in the pages of a good book.

But cultural observers always decry the debased tastes of youth. Our grandparents and great-grandparents fought for jazz and Joyce and D.H. Lawrence against the sneers of their elders. Young Romans flocked to hear Catullus and Ovid even as senators declared their poetry a threat to the commonwealth.

We are currently witnessing a flourishing renaissance of large narrative.

Beneath this traditional squabbling, several complaints are carelessly muddled together. One is the assumption that all electronic media are the same -- a widespread but naive view that is itself meat enough for several essays. Second, we have the equation of brevity with debased taste -- an equation that conveniently ignores the many short forms (haiku, sonnets, lieder, ink-brush calligraphy) which bear the acclaim of high culture. Third, the detractors assume that we live in an era of short forms and short attention spans. Observing the world as it is (rather than taking counsel of our fears), we can see that this is wrong: we are currently witnessing a flourishing renaissance of large narrative.

The Big Story

In 1955, J. R. R. Tolkien published The Lord of the Rings, a novel so massive that Allen and Unwin were forced to issue it in three volumes, reviving a tradition of multi-volume fiction that had lain quiet for generations. Tolkien's work was controversial and, in its time, rather difficult: written by a little-known Beowulf scholar, replete with obscure mythological references, and daunting in its sheer mass. Early readers either found it entirely admirable (W.H. Auden) or embarrassingly deficient in irony (Edmund Wilson); everyone found it . . . long. In time, though, Auden's judgement prevailed, and The Lord of the Rings staked its claim among the most important books of its era. In its wake, large novels, sometimes issued in thick volumes and sometimes as multivolume sets, flourish both in literary fiction (Durrell, Pynchon) and in commercial fiction (Michener, Clavell).

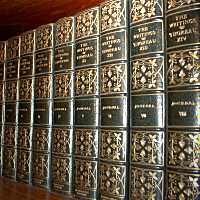

Love of the form of the book -- the smell of ink and leather -- is often an expression of nostalgia for an imagined past.

The braided serial novel, distributed piecemeal in magazines or pamphlets, enabled Dickens and his colleagues to tell stories that spanned hundreds of pages and whose telling consumed many months. Serial publication made good business sense, as it allowed readers to purchase a large book in small installments. Serial stories also allowed the audience to share (and discuss) the experience of an unfolding story over a substantial span of time: the unfolding of Dickens' tales became a social as well as a private phenomenon. In modern years, series fiction has served a similar function, allowing writers to craft narrative spaces of unprecedented size and detail while affording their readers space and time to talk about stories as they unfold. Writers as diverse as Updike, Le Carre, Patrick O'Brian, Raymond Chandler, and W. E. B. Griffin have all mined this vein. Kushner's Angels In America extends the same technique to theater: two very large plays, separately conceived and capable of separate performance, but tightly bound together and progressing naturally through a single huge narrative.

Babylon 5....a single narrative, conceived, written and produced almost completely by a single writer, presented in over 100 hours of performance

Television, too, has moved toward vast narratives. Television series have used a continuing premise for decades -- the wagon train striving to cross the West, the soap opera, the struggle of The Fugitive to escape pursuit -- but television tradition assumed that each episode should constitute an independent dramatic action. Steven Bochco's Hill Street Blues eroded this convention by letting narrative elements bleed outside the edges: a subplot established in one episode might remain unresolved, emerging as the central plot of a second episode and continuing to ramify through subsequent stories. John Straczynski's television epic, Babylon 5, currently nearing completion as I write, goes even farther: a single narrative, conceived, written and produced almost completely by a single writer, presented in over 100 hours of performance (equivalent to perhaps 50 feature films) over the course of five years.

Historical writing has also revived its interest in large narratives. Through much of this century, scope and detail were the province of the professional historian: Samuel Eliot Morrison's History of United States Naval Operations In World War II (15 volumes), though brilliantly written and easily accessible to the general reader, was long assumed too large for any save historians and naval officers. Recently, though, ever larger and more detailed works have reached broad audiences. Shelby Foote's three volume, 3000-page Civil War, and James McPherson's 904-page Battle Cry of Freedom, became best-selling texts of the American Civil War. Clay Blair's 1136-page history of the Korean War, The Forgotten War, and 1072-page history of American submarine operations in WWII Pacific, Silent Victory, were best-sellers. So, too, was Elkins and McKitrick's The Age of Federalism (925 pages), a title whose success is especially notable because it covers an unfashionable period and lacks an obvious narrative hook.

Scope and Scale

Too many pundits have confounded hypertext with television because both are viewed on screens. Whether on the Web or in the hand, hypertext isn't much like television: those who thought it was are now sifting through the rubble of Push.

pop culture adores huge tales

Many pundits, too, suppose that the patience for long stories is a mark of High Culture, an attribute of the intellectual elite. This is nonsense: pop culture adores huge tales. The contemporary fascination with celebrity reflects a taste for shared, social narratives that continue for months and years. Sports fans, too, follow teams and favorite players over long spans, for a single sporting season is long, the quest for the World Cup is longer still, and the arc of our favorite's career -- from rookie phenom to reigning star to wily veteran to front-office fixture -- may span decades.

The great surprise of the first decade of literary hypertext may well have been the emergence of short fiction at the center of hypertext writing. This must not blind us, however, to the importance of large narratives, or mislead us into believing that hypertext is a small medium suited to small sensations and small minds. The small minds belong to the pundits who fear the screen, and who cannot (or will not) see the worlds that lie beyond its glowing surface.